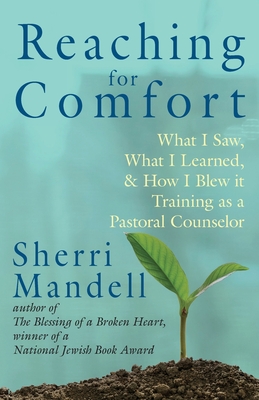

Reaching for Comfort: What I Saw, What I Learned, & How I Blew it Training as a Pastoral Counselor by Sherri Mandell

“I had gone to the dying to learn how to live. To find comfort. And all this time it was the world of the living…that had just as much to teach me.” In the subtitle of Sherri Mandell’s book, she notes that she “blew it training as a pastoral counselor.”

I am here to tell you she did not blow it; she has written a remarkable story of herself, a mother whose son was murdered (so different from ‘died,’ as she notes in her book) who managed to overcome the horrific loss of her son and comfort those, young and old, cognizant and comatose, who were in the hospital sick and suffering from illness or treatment.

“You don’t know how much I just want a normal life. I want to feed my kids, go to the movies, water plants, just normal things…Just the usual things-anything instead of being sick,” said a 49-year old female patient who Sherri called Liz. Sherri Mandell was in a training program to become a pastoral counselor, a novel approach at the time to help patients cope with serious illness and perhaps a dire prognosis, and was spending time in a hospital room with a young mother. The author’s own “normal life” had been cut short by the murder of her son and his friend: “On May 8, 2001, my 13 year-old son Koby cut school and went hiking with his friend Yosef Ish Ran in a canyon near our home in Israel. Terrorists trapped the two eighth-grade boys in a cave and beat them to death with rocks. The murderers smeared the boys’ blood on the walls of the cave.” Her college education, her lecturer position at the University of Maryland, her life as a wife and mother did not prepare her for what she “had to face. Nothing prepared me for loss.” To cope with her loss and bring some meaning and honor to her son and his friend, she and her husband established a sleepaway camp for “bereaved” Israeli children, Camp Koby, and founded the Koby Mandell Foundation to turn her son’s murder “into kindness.”

So Sherri (I feel as if I am as close to her as to other authors I’ve read) decided to help others even though “it was really me who needed help. Because I had another dream: I hoped that I would meet a guide there who would reveal to me the secret of how to emerge from the darkness.” She meets Reuven (all patients mentioned are “fictional composites”) who tells a remarkable story of his life as a successful American business man whose mistakes led him to conviction and prison and ill health and hospitalization; she is awkward in her attempts to comfort him and is chided by her training group for her efforts. She visits with Rena, a terminally ill mother whose son and daughter challenge her when she speaks of her own experiences rather than waiting for them to bring up a topic- a pastoral counselor faux pas. More patient visits follow- Vlada, who is closer to her aide than to her best friend; Musa, an Arab whose presence in the hospital gave the author pause as she flashed back to her son’s murderers, and Abe, the terminally ill patient whose wife Esther was “a character”- hiding her dementia behind eccentricity and teaching Sherri Mandell to “laugh at the lack of logic in this world, the way that so little made sense.”

My family will be surprised that I managed to read and review this book- my father, obm, passed away from a horrific brain tumor (is there any other kind?) when I was a young mother. To this day I find it difficult to discuss cancer or illness; I have fainted in hospitals (even in front of my young husband when he had his wisdom teeth out, a bona fide hospital stay back in the olden days) and need a sugary drink (a cold bottle of Coke works well, she notes from experience) to endure a visit to a hospital room. Sherri Mandell has taught me to accept the unacceptable: “I knew each person I had visited in the hospital had been like a length of rope that had led me to being able to dip a little deeper, so that I could finally bring the wooden pail to the surface and drink the refreshing water, to feel alive, to let go of the weight of my son’s dead body.” The author might have incrementally “blown it” in her pastoral counselor training, but she has excelled in bringing compassion to those who are ill, healing to herself during her profound loss, and optimism to those of us who have experienced loss, that we may put down our bottles of cold Coke and “drink that refreshing water” along with her.

May Koby and Yosef’s memory be for a blessing.

Randy Rubinstein lives in Sharon, Massachusetts